Send mail to Simon Quellen Field via leven@scitoys.com

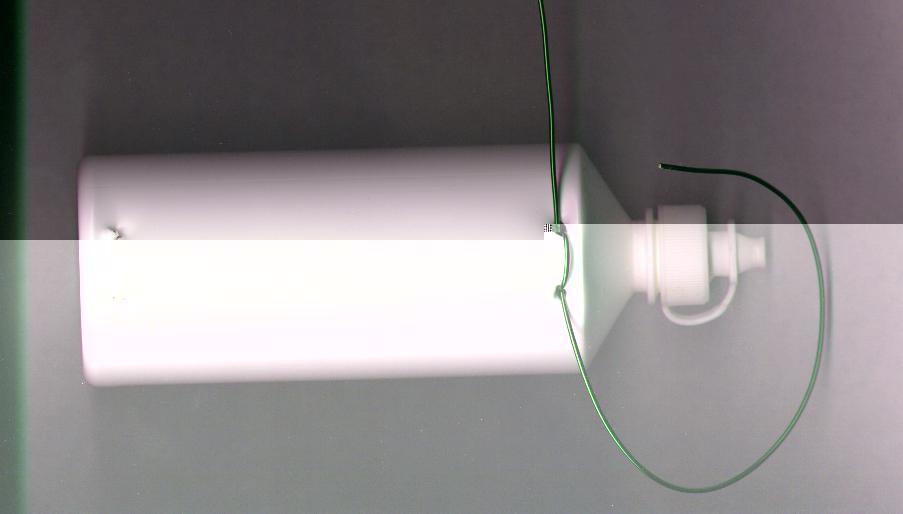

Thread the wire through the two holes at the top of the bottle, and pull

about 8 inches of wire through the holes. If the holes are large and the

wire is loose, it is OK to loop the wire through the holes again, making

a little loop of wire that holds snuggly.

Thread the wire through the two holes at the top of the bottle, and pull

about 8 inches of wire through the holes. If the holes are large and the

wire is loose, it is OK to loop the wire through the holes again, making

a little loop of wire that holds snuggly.

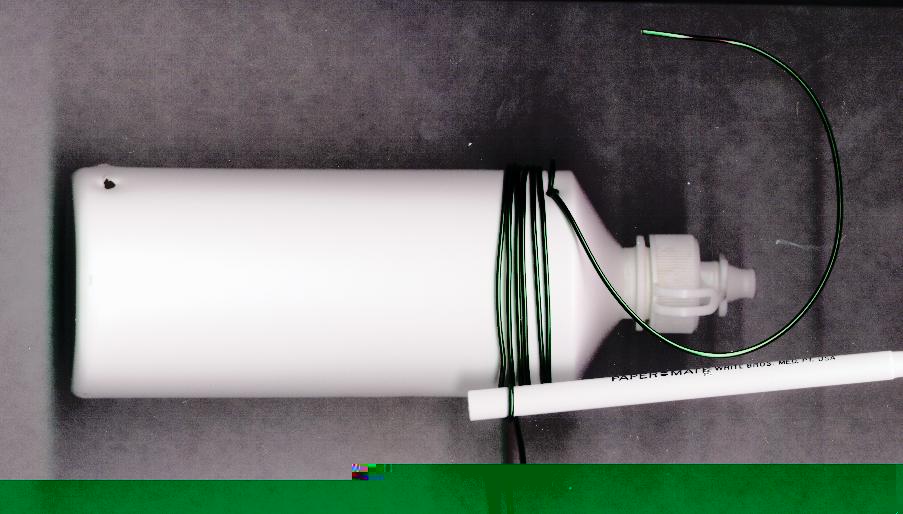

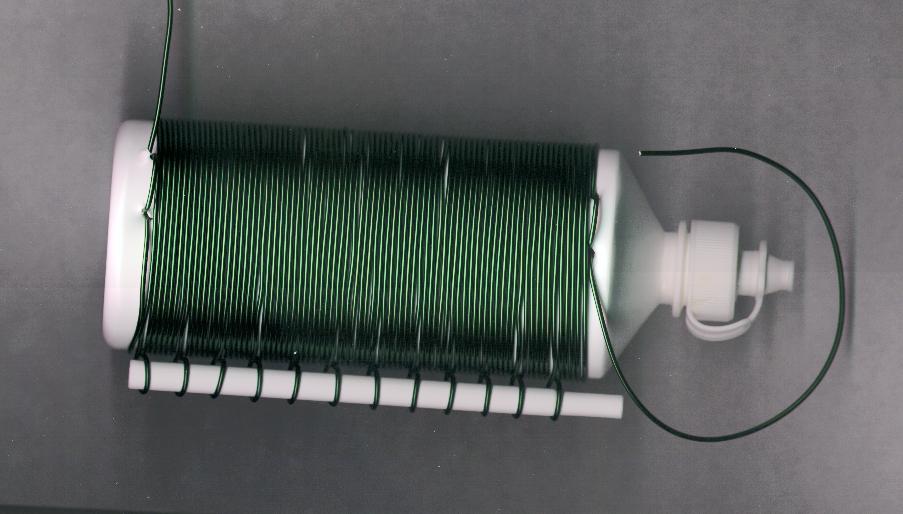

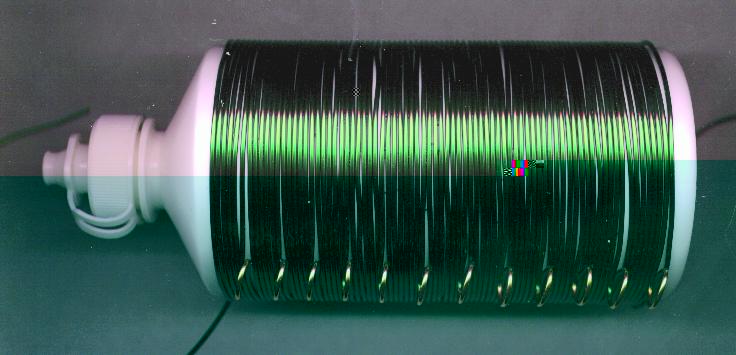

Now take the long end of the wire and start winding it neatly around the bottle.

When you have wound five windings on the bottle, stop and make a little loop

of wire that stands out from the bottle. Wrapping the wire around a nail or

a pencil makes this easy.

Now take the long end of the wire and start winding it neatly around the bottle.

When you have wound five windings on the bottle, stop and make a little loop

of wire that stands out from the bottle. Wrapping the wire around a nail or

a pencil makes this easy.

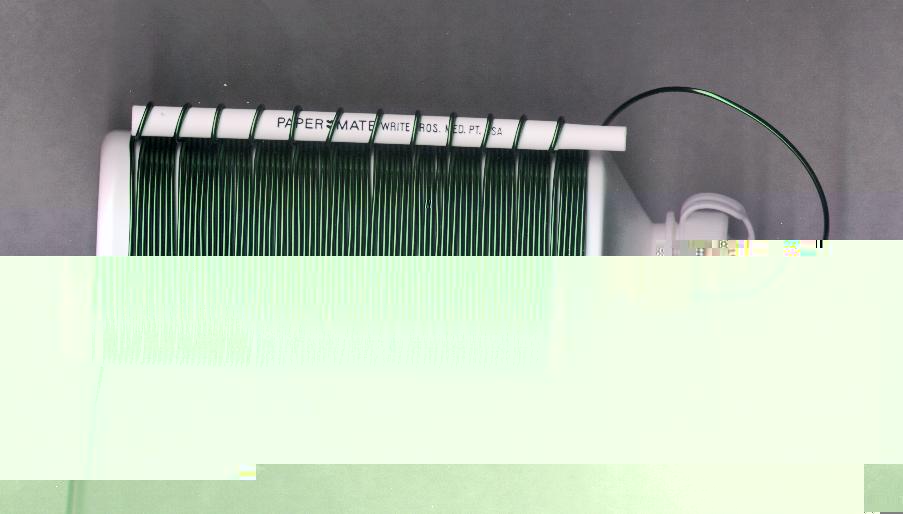

Continue winding another five turns, and another

little loop. Keep doing this until the bottle is completely wrapped in wire,

and you have reached the second set of holes at the bottom of the bottle.

Continue winding another five turns, and another

little loop. Keep doing this until the bottle is completely wrapped in wire,

and you have reached the second set of holes at the bottom of the bottle.

Cut the wire so that at least 8 inches remains, and thread this

remaining wire through the two holes like we did at the top of the bottle.

The bottle should now look like this:

Cut the wire so that at least 8 inches remains, and thread this

remaining wire through the two holes like we did at the top of the bottle.

The bottle should now look like this:

Now we remove the insulation from the tips of the wire, and from the small

loops we made every 5 turns (these loops are called 'taps'). If you are using

enameled wire, you can use sandpaper to remove the insulation. You can also

use a strong paint remover on a small cloth,

although this can be messy and smelly. Don't remove the insulation from the

bulk of the coil, just from the wire ends and the small loops.

If you are using vinyl coated wire, the insulation comes off easily with a

sharp knife.

Now we remove the insulation from the tips of the wire, and from the small

loops we made every 5 turns (these loops are called 'taps'). If you are using

enameled wire, you can use sandpaper to remove the insulation. You can also

use a strong paint remover on a small cloth,

although this can be messy and smelly. Don't remove the insulation from the

bulk of the coil, just from the wire ends and the small loops.

If you are using vinyl coated wire, the insulation comes off easily with a

sharp knife.

Next we attach the Germanium diode to the wire at the bottom of the bottle.

It is best to solder this connection, although you can also just twist the

wires together and tape them, or you can use aligator jumpers (Radio Shack

part number 278-1156) if you are really in a hurry.

Cut one end off of the handset cord to remove one of the modular telephone

connectors. There will be four wires inside. If you are lucky, they will

be color coded, and we will use the yellow and black wires. If you are

not lucky, the wires will be all one color, or one will be

red and the others will be white. To find the right wires, first strip off

the insulation from the last half inch of each wire. Then take a battery

such as a C, D, or AA cell, and touch the wires to the battery terminals

(one wire to plus and another to minus) until you hear a clicking sound

in the handset earphone. When you hear the click, the two wires touching

the battery are the two that go to the earphone, and these are the ones

we want.

The 'wires' in the handset cord are usually fragile copper foil wrapped

around some plastic threads. This foil breaks easily, sometimes invisibly,

while the plastic threads hold the parts together making it look like there

is still a connection. I recommend carefully soldering the handset wires

to some sturdier wire, then taping the connection so nothing pulls hard

on the copper foil.

Attach one handset wire to the free end of the Germanium diode.

Solder it if you can.

Attach the other wire to the wire from the top of the bottle.

Soldering this connection is a good idea, but it is not necessary.

Now clip an alligator jumper to the antenna.

Clip the other end to one of the taps on the coil.

Clip another alligator lead to the wire coming from the top of the bottle.

This is our 'ground' wire, and should be connected to a cold water pipe

or some other metal object or wire that has a good connection to the earth.

Next we attach the Germanium diode to the wire at the bottom of the bottle.

It is best to solder this connection, although you can also just twist the

wires together and tape them, or you can use aligator jumpers (Radio Shack

part number 278-1156) if you are really in a hurry.

Cut one end off of the handset cord to remove one of the modular telephone

connectors. There will be four wires inside. If you are lucky, they will

be color coded, and we will use the yellow and black wires. If you are

not lucky, the wires will be all one color, or one will be

red and the others will be white. To find the right wires, first strip off

the insulation from the last half inch of each wire. Then take a battery

such as a C, D, or AA cell, and touch the wires to the battery terminals

(one wire to plus and another to minus) until you hear a clicking sound

in the handset earphone. When you hear the click, the two wires touching

the battery are the two that go to the earphone, and these are the ones

we want.

The 'wires' in the handset cord are usually fragile copper foil wrapped

around some plastic threads. This foil breaks easily, sometimes invisibly,

while the plastic threads hold the parts together making it look like there

is still a connection. I recommend carefully soldering the handset wires

to some sturdier wire, then taping the connection so nothing pulls hard

on the copper foil.

Attach one handset wire to the free end of the Germanium diode.

Solder it if you can.

Attach the other wire to the wire from the top of the bottle.

Soldering this connection is a good idea, but it is not necessary.

Now clip an alligator jumper to the antenna.

Clip the other end to one of the taps on the coil.

Clip another alligator lead to the wire coming from the top of the bottle.

This is our 'ground' wire, and should be connected to a cold water pipe

or some other metal object or wire that has a good connection to the earth.

At this point, if all went well, you should be able to hear radio stations

in the telephone handset. To select different stations, clip the alligator

jumper to different taps on the coil. In some places, you will hear two or

more stations at once. The longer the antenna is, the louder the signal

will be. Also, the higher you can get the antenna the better.

Now that your radio works, you can make it look better and be sturdier

by mounting it on a board or in a wooden box. Machine screws can be

stuck into holes drilled in the wood to act at places to attach the

wires instead of soldering them. A radio finished this way looks like

the following photo. Note the nice little touch of using brass drawer

pulls on the machine screws to hold the wire.

At this point, if all went well, you should be able to hear radio stations

in the telephone handset. To select different stations, clip the alligator

jumper to different taps on the coil. In some places, you will hear two or

more stations at once. The longer the antenna is, the louder the signal

will be. Also, the higher you can get the antenna the better.

Now that your radio works, you can make it look better and be sturdier

by mounting it on a board or in a wooden box. Machine screws can be

stuck into holes drilled in the wood to act at places to attach the

wires instead of soldering them. A radio finished this way looks like

the following photo. Note the nice little touch of using brass drawer

pulls on the machine screws to hold the wire.